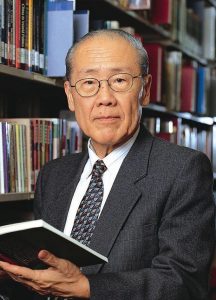

Modern China has been torn between affirming the integrity of its history despite the Sinocentric biases and accepting world history in the Eurocentric tradition. This ambivalence has not helped other people to understand China’s position in world history. Why this ambivalence? China obviously does not wish to accept a narrative that reads history backward, to take European history since the 17th and 18th centuries as norm. Together with other peoples with a strong heritage of their own past, the Chinese think it is unhistorical to impose one dominant narrative upon everyone’s past. Wang Gengwu, The Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History “现代中国在这两点之间徘徊:以汉文化为中心的国家历史,和以欧洲为中心的世界历史。何为矛盾?中国显然不希望接受一个逆向的历史叙述,把欧洲十七,十八世纪以来的历史当作规范。与世界上其他有强大文化遗产的人民一样,中国人认为把每个人的过去都强行纳入一个占统治地位的叙述方式违反了历史常识。” ____ 王赓武

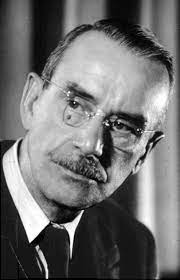

The nation, too, is not only a social but also a metaphysical being; the nation, not “the human race” as the sum of the individuals, is the bearer of the general, of the human quality; and the value of the intellectual-artistic-religious product that one calls national culture, that cannot be grasped by scientific methods, that develops out of organic depth of national life–the value, dignity and charm of all national culture, therefore, definitely lies in what distinguishes it from all others, for only this distinctive element is culture, in contrast to what all nations have in common, which is only civilization. Here we have the difference between individual and personality, civilization and culture, social and metaphysical life. The individualistic mass is democratic, the nation aristocratic. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, “国家也是一样,不仅是一个社会现实,也是一种形而上、非物质的存在。它不同于一群个人所形成的“人类”,而是一种基本人格素质的持有者,是大家所谓的那个国家文化,包括知识、艺术、宗教产物的价值。如何科学手段都无法抓住这个体系,因为它是从有机的国家历史发展中孕育而生的。所以国家文化的价值、尊严和感召力都来自它与其他文化的区别。正是因为这个明显的区别,才有了所谓的“文化”,不同于所有国家之间的相同之处,即“文明”。这就是个人与个性,文明与文化,社会存在于形而上的区别。个人的综合体是民主;国家则是皇贵。”

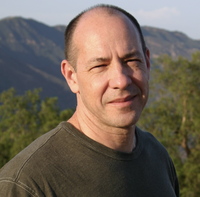

Above all, by dramatizing the violent and destructive process by which these archaic societies are transformed by and incorporated into the modern world, these four novelists (Hardy, Conrad, Achebe, and Llosa) testify to the havoc wreaked upon individual human lives in the name of progress. The novelists I discuss are all citizens and beneficiaries of the modern world, but they nonetheless felt compelled to record for posterity the great costs, paid in blood and pain, the peoples around the world have rendered to settle accounts with history. Michael Valdez Moses, The Novel and the Globalization of Culture “最重要的是,这四位小说家(哈代、康拉德、阿契贝和略萨)通过戏剧化地展现这些古老社会被现代世界改造并融入其中的暴力和破坏性过程,见证了以进步的名义对个人生命造成的浩劫。我所讨论的这些小说家都是现代文明的公民和受益者,但他们仍然感到有必要为后世记录下世界各国人民为清算历史而付出的巨大代价,这些代价包括鲜血和痛苦。” 麦克.默思《小说与全球化》

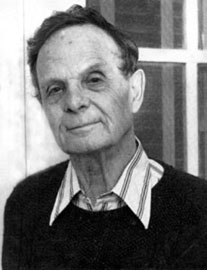

The Disease Called Man. … Stated in more general terms, the essence of repression lies in the refusal of the human being to recognize the realities of his human nature. … Why does man, of all animals, have a history? For man is distinguished from animals not simply by the possession and transmission from generation to generation of that suprabiological apparatus which is culture, but also, if history and changes in time are essential characteristics of human culture and therefore of man, by a desire to change his culture a d so to change himself. … Then the historical process is sustained by man’s desire to become other than what he is. And man’s desire to become other than what he is. …Mankind today is still making history without having any conscious idea of what it really wants or under what conditions it would stop being unhappy. In fact, what it is doing seems to be making itself more unhappy and calling that unhappiness progress. …Psychoanalysis can provide a theory of “progress”, but only by viewing history as a neurosis. Life against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History “名为“人”的疾病……更笼统地说,压抑的本质在于人类拒绝承认其人性的现实。……为什么在所有动物中,人有历史?因为人与动物的区别不仅在于拥有并代代相传的超生物机制——文化,而且——如果历史和时间的变迁是人类文化的本质特征,因此也是人的本质特征——还在于人渴望改变其文化,从而改变自身。……因此,历史的进程是由人想要改变自身的意愿而支撑的。而人渴望成为不同于自身的样子。……今天的人类仍在创造历史,却没有意识到自己真正想要什么,也没有意识到在什么条件下自己会不再感到不快乐。事实上,人类所做的似乎正在让自己变得更加不快乐,并将这种不快乐称为进步。……精神分析学可以为“社会进步”提供一个理论,但前提是将历史视为一种神经病。”

“But in India, it [despotism] is normal: for here there is no sense of personal independence with which a state of despotism could be compared, and which would raise revolt in the soul; nothing approaching even a resentful protest against it, is left, except the corporeal smart, and the pain of being deprived of absolute necessaries and of pleasure. In the case of such a people, therefore, that which we call history is not to be looked for. … This [Hinduism] makes them incapable of writing history; all that happens is dissipated in their minds into confused dreams.” Georg Wilhelm Frederick Hegel, The Philosophy of History 黑格尔《思想史》“但是在印度,专制是常态。在这并不存在与其形成鲜明对照的个人独立信念,可以引起在灵魂深处的反抗精神。除了肌肤的疼痛,求生的基本需求和寻欢作乐的念想,连一丝抗拒的意思都剩不下。在这样一个民族,我们所谓的历史是根本找不到的。印度教使他们没有可能写历史。所有发生的事件都被当作杂乱无章的梦而忘却,消失的一干二净。”

This, then, is our task. We men of the Western Culture are, with our historical sense, an exception and not a rule. World-history is our world picture and not all mankind’s. Indian and Classical man formed no image of a world in progress, and perhaps when in due course the civilization of the West is extinguished, there will never again be a Culture and a human type in which “world-history” is so potent a form of the waking consciousness. … For primitive man the word ‘time’ can have no meaning. He simply lives, without any necessity of specifying an opposition to something else. He has time, but knows nothing of it. All of us are conscious of space only, and not of time. …Time is a counter-conception of Space. …Western history was willed and Indian history happened. The Decline of the West “这就是我们的任务。我们西方文化的人,凭借着我们的历史感,是一个例外,而非常态。世界历史是我们的世界图景,而非全人类的世界图景。印度人和古典人并没有形成一个正在进步的世界的形象,或许,当西方文明最终消亡时,将不再存在一种文化和一种人类类型,在其中,“世界历史”是如此有力的清醒意识形式。……对原始人来说,“时间”一词毫无意义。他只是活着,无需与其他事物其他人进行抗争。他拥有时间,却对时间一无所知。我们所有人只意识到空间,而不是时间。……时间的对立概念是空间。……西方历史表达的是人的意志,而印度历史仅仅是发生了。”

Modern man no longer communicates with the madman … There is no common language, or rather, it no longer exists; the constitution of madness as mental illness, at the end of the eighteenth century, bears witness to a rupture in a dialogue, gives the separation as already enacted, and expels from the memory all those imperfect words, of no fixed syntax, spoken falteringly, in which the exchange, between madness and reason, was carried out. The language of psychiatry, which is a monologue by reason about madness, could only have come into existence in such a silenceve. 《疯癫与文明》Madness and Civilization) “现代人不再与疯癫人交流。他们之间不再存在一种共同的语言。… … 到了十八世纪末,精神失常作为一种疾病见证了一种对话的终结,实行已久的隔离方式得以正式实施,之前疯癫与理性沟通所要依赖的含糊不清、颠三倒四、语无伦次的表达被从人类的记忆中驱逐干净。取而代之的是精神分析的专业术语;在这种寂静中,它无异于一种理性关于疯癫的独白。”

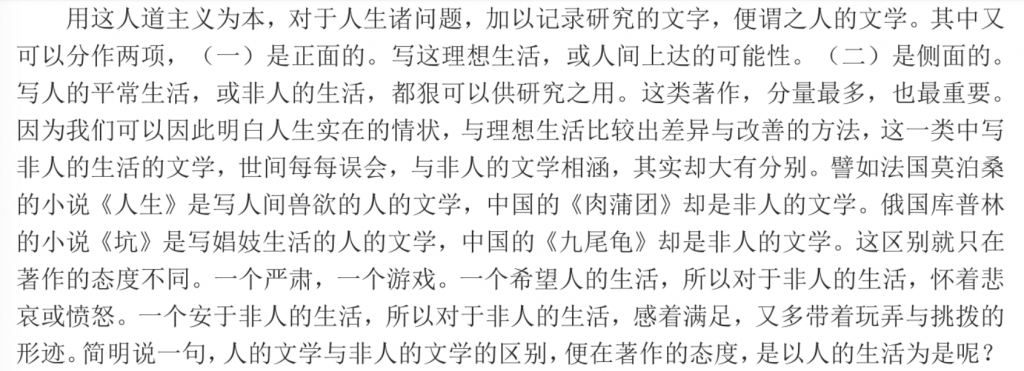

For instance, the Frenchman Maupassant’s Une Vie is human literature about the animal passions of man; China’s Prayer Mat of Flesh, however, is a piece of non-human literature. The Russian Kuprin’s novel Jama is literature describing the lives of prostitutes, but China’s Nine-tailed Tortoise is non-human literature. The difference lies merely in the different attitudes conveyed by the work, one is dignified and one is profligate; one has aspirations for human life and therefore feels grief and anger in the face of inhuman life, whereas the other is complacent about human life, and the author even seems to derive a feeling of satisfaction from it, and in many cases to deal with his material in an attitude of amusement and provocation. In one simple sentence: the difference between human and non-human literature lies in the attitude that informs the writing; whether it affirms human life or inhuman life. Zhou Zuoren, Humane Literature

欧洲有了十八九世纪的个人主义,造出了无数爱自由过于面包,爱真理过于生命的特立独行之士,方才有今日的文明世界。现在有人对你们说:“牺牲你们个人的自由,去求国家的自由!” 我对你们说:“争你们个人的自由,便是为国家争自由!争你们自己的人格,便是为国家争人格!自由平等的国家不是一群奴才建造得起来的!” 胡适《介绍我自己的思想》1930; In Western Europe during the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries, there was individualism that was responsible for today’s civil world, built by countless people who loved freedom more than bread, and who cared more about truth than their own life. Now some say to you, ‘Sacrifice your personal freedom to fight for the freedom of the nation!’ But I say to you: ‘Fighting for your own individual freedom is fighting for the freedom of your nation! To fight for your own dignity is to fight for the dignity of the nation!’ A nation of freedom and equality cannot be built by a group of slaves. Hu Shi, Introducing My Own Thinking 1930;

学者,刘若愚,“在同一语言体系中进行演绎的批评家已经面临足够的难题了,那些跨语种的批评家则要面临双倍的难题。这是因为除了不同历史年代之间的区别,他们还要照顾到语言和语言,文化和文化之间的差异。跨语种的文学批评家得决定自己对待这些差异和许别应采取的态度;因为这会决定他将作出的演绎和评判。这绝不是一个容易的决定。即便是在一个单一的文化或文学传统中也存在相互冲突矛盾的阐释学。… … 在文学批判上,评论家也面临同样的一组态度和立场的选择:汉学中心论、欧洲中心论、文化相对论、文化决定论、跨文化视角。我在这回避“文化沙文主义”和“种族主义”等字眼,不去涉及评论家的文化和身份认同。” “The problems of interpretation facing an intralingual critic are formidable enough: they become doubly so for the interlingual critic, since to the problems due to differences between historical periods are added those due to cultural and linguistic differences. The interlingual critic has to make a decision as to what basic attitude he should take toward such differences, and the decision will determine the kind of interpretation that he will offer. It is not an easy decision to make, for even within a single cultural and literary tradition there can be conflicting schools of hermeneutics. . . . With regard to the interpretation of Chinese literature, the critic has a similar set of attitudes to choose from: Sino-centrism, Eurocentrism, cultural relativism, cultural perspectivism and trans-culturism. I am avoiding the term “cultural chauvinism” or “ethnocentrism” so that the critic’s own cultural and ethnic identity need not be called into question.” James Y. Liu, The Interlingual Critic

The ubiquitous potential presence of a balanced, totalized, dimension of meaning may partially explain why a fully realized sense of the tragic does not materialize in Chinese narrative. …. But in each case the implicit understanding of the logical interrelation between these fictional characters’ particular situation and the overall structure of existential intelligibility serves to blunt the pity and fear the reader experiences as he witnesses their individual destinies. In other words, Chinese narrative is replete with individuals in tragic situations, but the secure inviolability of the underlying affirmation of existence in its totality precludes the possibility of the individual’s tragic fate taking on the proportions of a cosmic tragedy. Instead, the bitterness of the particular case of mortality ultimately settles back into ceaseless alternation of patterns of joy and sorrow, exhilaration and despair, which go to make up an essentially affirmative view of the universe of experience. Andrew Plaks, Chinese Narrative;“这个平衡的、整体的文化维度无处不在,这或许可以部分解释中国叙事传统为什么未能充分体现悲剧感。……但在每种剧情中,这些虚构人物的特定处境与存在主义阐释学之间隐含的逻辑关系,有助于淡化读者在见证他们个人命运时所体验到的怜悯和恐惧。换言之,中国叙事充斥着身处悲剧境地的个体,但其对整体存在的基本肯定是不可违反的,这就排除了个体悲惨命运构成宇宙性悲剧的可能性。相反,具体死亡案例的痛苦最终回归到喜悦与悲伤、兴奋与绝望模式的不断交替中,这些模式构成了对人间经历的一种肯定态度。”

This distortion [on the part of the Twentieth-Century scholars] conveys the impression that the Chinese gender system was built upon coercion and brute oppression, which, in my view, ascribes to it at once too much and too little power. The strength of resilience of the gender system—as it unfolded in history, not on pages of codes of conduct—should be attributed to the considerable range of flexibilities that women from various classes, regions, and age groups enjoyed in practice. … The complex and ambivalent existence of women in the Confucian tradition can be illuminated only when the propensity to treat ‘Confucianism’ as an abstract creed or a static control mechanism is discarded. The Confucian tradition is not a monolithic and fixed system of values and practices. … Contrary to the popular perception that gender relations belong to the feudal backwaters, my contention is that they constitute the most enabling aspect of Chinese tradition. The contestations over the meaning of modernity today would be more meaningful if tradition were being re-imagined as a series of trade-offs, and both its strengths and weaknesses were being confronted seriously. If Chinese modernity cannot be defined as the negation of tradition, then the unusual historical moment we have witnessed–the seventeenth century–is instructive in showing how tradition can be harnessed to further untraditional goals, and how women can be incorporated into new ways of imagining national and local communities. In these ways, the ‘teachers of the inner chambers’ still have much to teach the Chinese nation today. Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China;“这种(二十世纪学者的)扭曲给人留下了这样一种印象:中国的性别制度建立在强制和残酷压迫之上,在我看来,这既赋予了它过多的权力,也赋予了它太少的权力。性别制度的韧性——它体现在历史中,而非行为准则的篇章中——应该归功于不同阶级、地区和年龄段的女性在实践中享有的相当大的灵活性。……只有摒弃将“儒家思想”视为抽象信条或静态控制机制的偏见,才能阐明儒家传统中女性复杂而矛盾的存在。儒家传统并非一套一成不变的价值观和实践体系。……与被普遍接受的封建落后性别关系的看法相反,我认为它们构成了中国传统中最有创意的方面。如果将传统重新想象为一系列的权衡,并认真审视其优势和劣势,那么当今关于现代性意义的争论将更有意义。如果中国的现代性不能被定义为对传统的否定,那么我们所见证的十七世纪这一非同寻常的历史时刻,就具有了一种启发意义,它展现了如何利用传统来推进非传统的目标,以及如何将女性融入到构想国家和地方共同体的新方式中。从这些方面来看,‘内阁之师’至今仍有许多可以传授给今天的中华民族。”

“The Bourgeois limitations in feminist theory are clearly demonstrated by its difficulty in dealing with prostitution, which is interpreted solely in outworn terms of victimization. That is, feminists profess solidarity with the “sex workers” themselves but denounce prostitution as a system of male exploitation and enslavement. I protest this trivilizing of the world’s oldest profession. I respect and honor the prostitute, ruler of the sexual realm, which men must pay to enter. In reducing prostitutes to pitiable charity cases in need of their help, middle-class feminists are guilty of arrogance, conceit, and prudery. …It is a progressive feminism that embraces and celebrates all historical depictions of women, including the most luridly pornographic. It wants mythology without sentimentality and every archetype, from mother to witch and whore, without censorship. It accepts and welcomes the testimony of men.” Camille Paglia, Vamps and Tramps;“中产阶级在女权主义理论上的局限性,在其难以处理的卖淫问题上,体现得淋漓尽致。人们仅仅用已经过时了的受害者视角来解读卖淫。也就是说,女权主义者声称与‘性工作者’团结一致,却又谴责卖淫是一种男性剥削和奴役他人的社会体系。我抗议这种对世界上最古老职业的蔑视。我尊重并敬畏妓女,她们是性领域的统治者,男性必须付费才能进入。中产阶级女权主义者将妓女贬低为需要她们帮助的可怜施舍对象,证实了他们的傲慢、自负和假正经。……这是一种进步的女权主义,它拥抱并赞美所有历史上对女性的描述,包括最耸人听闻的色情描写。它想要没有感伤的神话和所有生存原型,从母亲到女巫和妓女,都不受审查。它接受并欢迎男性的证言。”

Appeals to the past are among the commonest of strategies in interpretations of the present. What animates such appeals is not only disagreement about what happened in the past and what the past was, but uncertainty about whether the past really is past, over and concluded, or whether it continues, albeit in different forms, perhaps. This problem animates all sorts of discussions—about influence, about blame and judgment, about present actualities and future priorities. … The relatively common denominator between the various aspects of Orientalism is the line separating Occident from Orient and this is less a fact of nature than it is a fact of human production, which I have called imaginative geography. This is, however, neither to say that the division between Orient and Occident is unchanging nor is it to say that it is simply fictional. Edward Saïd, Orientalism Reconsidered,“追述过去是解释当下最常见的策略。这种吸引力不仅仅来自对过去的不同看法或者是否真实,而且关系到过去是否已经真的成为过去,还是可能以其他的形式继续。这个问题激活了各种各样的讨论,关于影响,责备,判断,关于当下的现实和对未来事件的轻重缓急。… … 东方主义的各种学派有一个共同点,把东西方分开;这与其说是一个事实,还不如说是一个文化构造。我称它为‘想象出来的地理学’。这并不是说东西方的区别是一成不变的,也不是说它纯粹是一个虚幻。”

Nations, like narratives, lose their origins in the myths of time and only fully realize their horizons in the mind’s eye. Such an image of the nation–or narration–might seem impossibly romantic and excessively metaphorical, but it is from those traditions of political thought and literary language that the nation emerges as a powerful historical idea in the West. … A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-day consent, the desire to live together, the will to perpetuate the value of the heritage that one has received in an undivided form. Man does not improvise. The nation, like the individual, is the culmination of a long past of endeavors, sacrifice, and devotion. . . . A nation is therefore a large-scale solidarity, constituted by the feeling of the sacrifices that one has made in the past and of those that one is prepared to make in the future. It presupposes a past; it is summarized, however, in the present by a tangible fact, namely, consent, the clearly expressed desire to continue a common life. A nation’s existence is, if you will pardon the metaphor, a daily plebiscite, just as an individual’s existence is a perpetual affirmation of life. Homi Bhabha, Nation and Narration;“叙述的源头常常消失在历史时代的神话中,它的地平线只有在人们的心目中才变得依稀可见。国家也是一样。这种对国家和叙述的比喻听起来似乎非常浪漫或不着边际,但在西方,国家作为一个强有力的概念确实是从一些政治和文学传统中脱颖而出的。… … 国家由这样两个东西组合成为一体:一个魂灵,一个精神原则。它们一个身处过去;另一个坐落在当下。一个作为文化记忆被大家持有;另一个是当今大家的共识,愿意同甘共苦来坚守大家一起继承下来的价值观。人类不善于临场做戏。国家作为一个整体为人们在过去经历的牺牲和作出的贡献告终。因此,国家是一个规模巨大的同盟,把人们以前所做出过和以后将要做出的牺牲凝聚在一起。国家需要假设一个过去,以此来总结当下触手可及的现实需要,表达大家将相依为命的意愿。国家经历,如不介意这个比喻,无异于每日的全民公决;就像人过的每一天都是在肯定永恒的生命。”